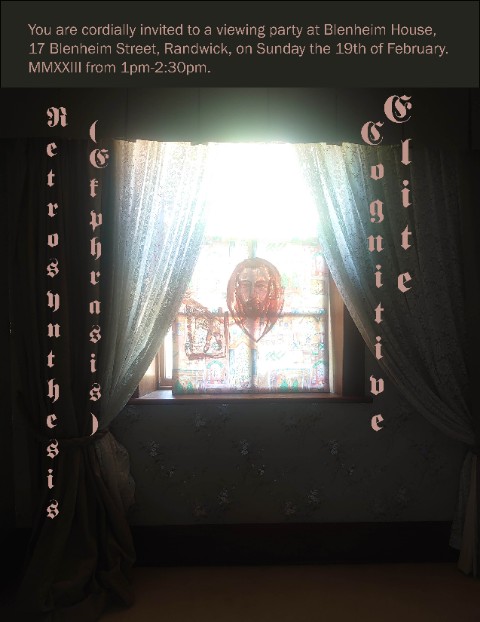

“Retrosynthesis(Ekphrasis): The Cognitive Elite” at Blenheim House, Randwick

Overview, Photograph: Jessica Maurer.

Overview, Photograph: Jessica Maurer.Ekphasis:

Directly below there is a series of explainations as to why these paintings happened, that may or may not be misleading. The idea of ekphrasis, to learn between disciplines like this appealed to my sense that sometimes things were better painted, better written. I realised that I have always made paintings as a way of understanding the world, which is why I do not concern myself so much with their alleged end-goal as luxury goods. I make them for myself and I think about things as I look at them and they are mine. I make them out of waste products and they are cheap and very precious to me. These paintings can be explained in many different ways, perhaps as one would use a Powerpoint, but more layered, textural. They are also much better in person. Realising that there is something fundamentally oral about my “writing”, I come to terms with the way that I organise things through refrain, an a-chronology like in an epic poem with occassional image to jog memory.

“The Cognitive Elite” is a term favoured by billionaire, Peter Thiel, describing “innovation”. It was quite funny to me as someone cognitively impaired, and seeing as this “elite” seems to look a lot like it always had (despite our best efforts at representation). So I paint them, these invisible rulers alongside the invisible thinkers and artists. The subjects are sometimes awful sometimes excellent, a throughly ambivalent insight into things and people that I am thinking about. I would not paint the “others” among the artists and thinkers because we are watched quite enough, and our objectivity challenged by the objectification. I wanted the room to overwhelm the viewer with a sense of mens’ eyes upon them, sharing my experience like a novel of old.

“Counterpoise (Varoufakis Vittorioso)” MMXXIII.

“Counterpoise (Varoufakis Vittorioso)” MMXXIII. Acrylic on found board. Photograph: Jessica Maurer.

“Another Reformation Meat Diet: The Princes (Looks/Trade-off)” MMXXIII.

“Another Reformation Meat Diet: The Princes (Looks/Trade-off)” MMXXIII.Acrylic on (discarded) board. Photograph: Jessica Maurer.

“Pure Colonial Backwaters/Academic Art (Don’t Cross Daddy)” MMXXIII.

“Pure Colonial Backwaters/Academic Art (Don’t Cross Daddy)” MMXXIII.Acrylic on (found) (drawing) board. Photograph: Jessica Maurer.

“Shaking the Penis Tree (Jan Verwoert sex dream after the Massa Marittima Mural, lockdown 2020)” MMXXIII.

“Shaking the Penis Tree (Jan Verwoert sex dream after the Massa Marittima Mural, lockdown 2020)” MMXXIII.Oil, rabbit-skin glue, stretched poly/cotton. Photograph: Jessica Maurer.

Photograph: Jessica Maurer.

“(Projection) Aesthetic Ascetic: Christ on a Wine Press” MMXXIII.

“(Projection) Aesthetic Ascetic: Christ on a Wine Press” MMXXIII.Lime wash, stretched cotton (discarded bed sheet). Photograph: Jessica Maurer.

Detail: “(Projection) Aesthetic Ascetic: Christ on a Wine Press” MMXXIII.

Lime wash, stretched cotton (discarded bed sheet).

“Cultural Capital/Sun King (Hipster Fascism)” MMXXIII.

“Cultural Capital/Sun King (Hipster Fascism)” MMXXIII.(Found) Masonite, acrylic. Photograph: Jessica Maurer.

“Print Screen (Cast-Light Horology)” MMXXIII.

“Print Screen (Cast-Light Horology)” MMXXIII.Oil on (discarded) glass. Photograph: Jessica Maurer.

“(Projection) On Reflection,” MMXXIII.

“(Projection) On Reflection,” MMXXIII.Oil on glass. Photograph: Jessica Maurer.

Photograph: Jessica Maurer.

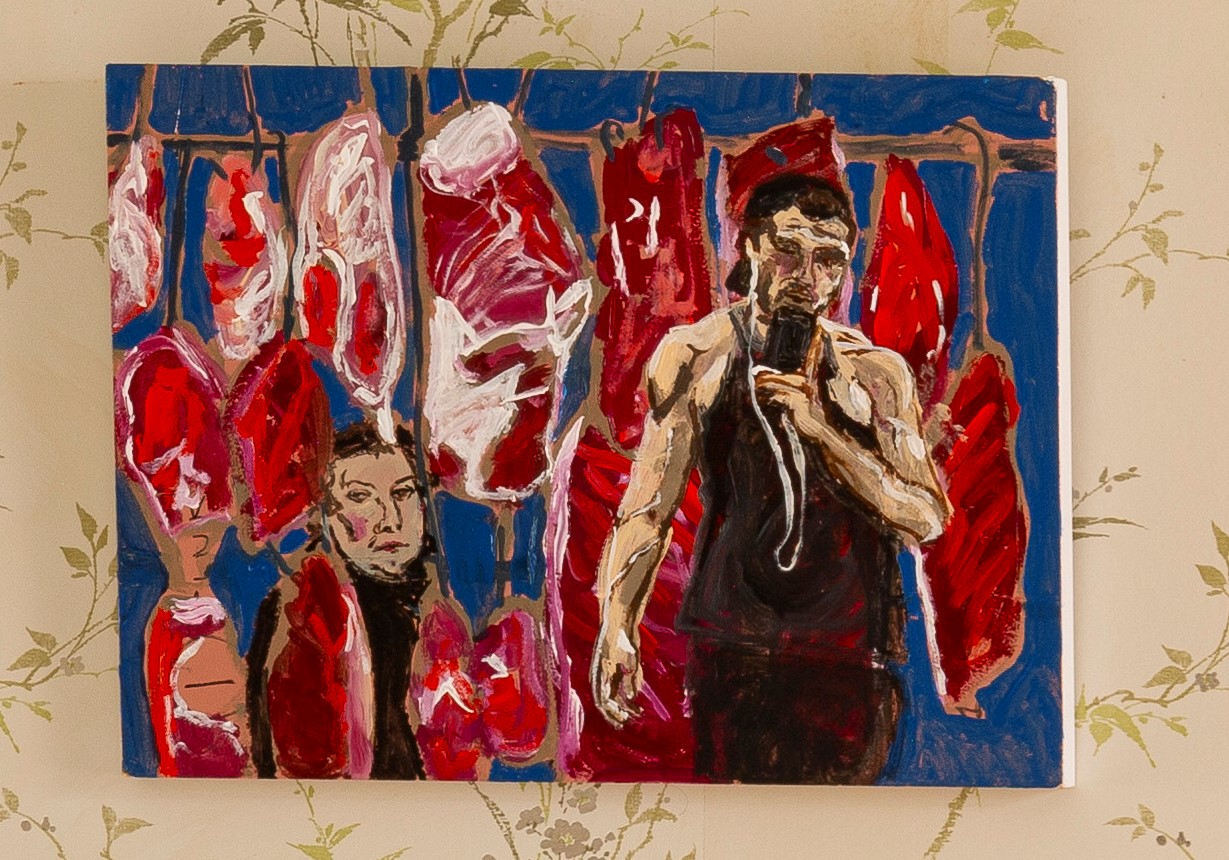

Photograph: Jessica Maurer. “Distribution/Consumption (Blue Origin of the Gods),” MMXXIII

“Distribution/Consumption (Blue Origin of the Gods),” MMXXIII

(Found) Masonite, acrylic. Photograph: Jessica Maurer.

“Benevolence (The Emperor’s New Clothes/You Can Leave Your Hat On) ” MMXXIII.

“Benevolence (The Emperor’s New Clothes/You Can Leave Your Hat On) ” MMXXIII.Acrylic on (found) (drawing) board. Photograph: Jessica Maurer.

Photograph: Jessica Maurer.

On “Academic Art”

The following text explains the painting that explains the text. It is part of a larger project called Ekphrasis//Ekphrasis which I will be publishing on Substack.

On Academic Art:

by Zoë Marni Robertson

EKPHRASIS:

“Pure Colonial Backwaters/Academic Art (Don’t Cross Daddy)” MMXXIII.

“Pure Colonial Backwaters/Academic Art (Don’t Cross Daddy)” MMXXIII.Acrylic on (found) (drawing) board. Photograph: Jessica Maurer.

ABSTRACT/SYNOPSIS (BROAD STROKES):

In "Pure Colonial Backwaters/Academic Art (Don't Cross Daddy/Hlodewig)” Post-internet artist Simon Denny sits atop the tomb-like raft of the “Sons of Clovis II”, a 19th century “History Painting” owned by (and on, apparently permanent, prominent display in) the Art Gallery of New South Wales. 19th century “History Painting” (also known as “Academic Art”) is a much-maligned movement (or term that straddles a few movements) that basically refers to paintings with very literal and ‘realistic’ interpretations of historical (or allegedly historical) events. The source painting, by Évariste Vital Luminais, depicts sons that have risen up against their father only to be “hamstrung” (have their tendons severed) by their mother, Saint Bathilde, in retaliation, a story cobbled-together from others from early French history (the Merovingian dynasty which began around the 5th Century, after the fall of the Roman Empire). Luminais was referred to variously as the painter of the Franks and the Gauls, popular after the revolution for depictions like these of Frankish brutality (because they had apparently decapitated the Franks during the revolution leaving the innocent Gauls to rule)(who were then brutality suppressing populations elsewhere). So much of the work being produced lately conforms to the ideals of 19th century History Painting/Academic Art in quite literally representing its source material and intentions (though in ways that are more formally more divergent). Denny’s exhibition “The Founder’s Paradox” delves heavily into material surrounding Silicon Valley Billionaire Peter Thiel’s purchase of 190 hectares of land around Lake Wanaka in Aotearoa. Thiel’s intention was to build a doomsday property in which to outlive the collapse of society. Denny demonstrates the theory that is the background for this in artworks in the aesthetic of board games, pitting Thiel’s Techno-Libertarianism against another possible scenario modelled on cooperation. In “Pure Colonial Backwaters…)” the sons of Clovis II float near-death on the pure waters of Lake Wanaka unaided by the artist/observer atop their lifeboat as the world descends into a brutality that Billionaires such as Thiel champion. It almost seems as though the Contemporary artist is also, if not actually, hamstrung, in the necessity of creating “subversive” work that will appeal to the market.

EKPHRASIS:

PAINTING AS HOAX:

An Australian art historian once quipped that “The Sons of Clovis II” was a fitting purchase for the Art Gallery of New South Wales as a reminder of what happens to naughty children.[1]This is mentioned in a book which takes its title from the painting, dissecting Australia’s largest literary hoax, the “Ern Malley Affair” (with reference to a 19th Century French literary hoax Adore Floupette the fictional Symbolistepoet whose first poem refers to the other “Sons of Clovis” painting: “Les Enerves Jumieges”). According to Blue-Mountains-based artist Ian Milliss, “The Sons of Clovis II” was/is a pilgrimage for the hungover of Sydney[2](fitting for its origins in 19th century French salons).

Aside from “The Sons of Clovis II”, one of the major attractions of The Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW), and the most visited exhibition, is that of Australia’s richest art prizes: The Archibald (for portraiture of prominent Australians), The Wynne prize (for landscape) and The Sir John Sulman (for murals/subject/genre paintings i.e., History Painting), which run concurrently before touring the country.

Photo of Simon Denny by Sebastian Kim for Interview Magazine, November 29, 2011.

BACKWATERS:[3]

Rereading about Billionaire Peter Thiel’s Aotearoa/New Zealand “doomsday” property and Denny’s exhibition on the subject, “The Founders Paradox”,[4]while thinking about the references to the pure, clean waters of Lake Wanaka, lead to the strange conflation of these works (i.e., “The Founders Paradox” and “The Sons of Clovis II”). Thiel was famously the only person in Silicon Valley to donate to the Trump Campaign,[5]a believer in some strange theories concerning the kind of doomsday prepping that would allow for Billionaires to basically carry on business-as-usual after the apocalypse,[6]and sometime backer of internet-alternative “Urbit”, with its stated aims toward a feudal system of online governance.[7]The static view of the “pristine” environment of Aotearoa/New Zealand, continually referred to by Billionaires (several of whom have bought property there for when the world grows more uninhabitable), would seem to suggest that it will always be so, as though the world is not alive, and there is somewhere far enough away that you could wait out the end of humanity without being affected by it. It is the lot of the Antipodean to always be positioned at the end of the world (the word itself means something like “their feet against our feet”). In the aforementioned exhibition by Denny, two separate spaces contained the two representations of possible political alternatives; pitting the game-like competitive futures favoured by Silicon Valley, against an alternative as postulated in an (Aotearoa/New Zealand) best-seller “The New Zealand Project” by Max Harris, apparently “a blend of old Keynesian economics and modern millennial values”[8]that is “influenced by Māori beliefs about society.”[9] The “binary opposition” of these views (apparently) largely summed up by hostility-to or belief-in broader state control (Techno-Libertarianism versus the Welfare State).[10]Denny’s art objects are essentially modelled on tools of “Visual Communication” reproducing the clean professionalism of toy companies or museums directed towards the education of minors, they are perfectly ugly. What is offered is a kind of suite of merchandise surrounding the (as Peter Thiel himself pointed out “meticulous”[11]) research. And, though the work does not necessarily speak to any inherent acceptance that “Small Government” and “Big Government” are the only considerations for political futures, the formal aspect engenders the kind of trust that is built into the design of educational materials, as we are taught to accept them.[12]The apparent acceptance that these two options represent polar opposites is perhaps troubling: John Maynard Keynes, was, after all, considered a conservative,[13]before the current era (from roughly after the 1980s) of generalised acceptance of free-market economics. By presenting an alternative future whose “left” politics are what would traditionally be considered conservative we have a reflection of the current situation where “the centre” is seen as the happy medium, and yet it is somewhere much further “right” than the policies of conservative governments during the 1970s. (This is not to disagree with the ideals of the Harris Project.)[14]But then, perhaps the point of “The Founder’s Paradox” is that in these “doomsday” projections “the right” provide no real alternative, no future, so much as violent ends (Thiel was said to find the black mirror reflection of his values quite unsettling).[15] On the other hand, a quote from one of Harris’ (most grumpy) critics argues against the same perceived inefficacy of Harris’ vision, in a way that seems to fit seamlessly with Denny’s exhibition: “All the talk about What Must Be Done starts to feel less like activism and more like a form of fantasy roleplaying, only instead of pretending to be dragon-slayers, or vampires, progressive intellectuals pretend to be people who are relevant to contemporary politics.”[16]

Perusing the (sometimes very thick) volumes attached to Denny’s numerous major exhibitions, one thing that stands out is that (in these exhibitions whose very work necessitates thorough research) the essays are generally written by people other than Denny himself. It is as though Denny functions as not so much an academic, but as a one-man Arts Faculty. “The Founders Paradox: A Compendium” was written by Art critic and writer Anthony Byrt, who, begins by explaining that he was widely quoted after the publication of his 2011 book “This Model World”, after writing that: “I have never been able to entirely figure out whether (Denny) is a critic of the corporate neoliberalism that provides him with so much of his subject matter, or an artist deeply embedded within, and beholden to, that system.”[17](One might say, cynically, that coming to work with and even employ one’s critic is in itself a classic Neoliberal strategy.) Perhaps the major issue with the humanities being put-to-work in this way is evidenced in what passes for a literature review in which Byrt (without explanation) quite blithely endorses and dismisses major recent works of internet-centric theory (Angela Nagle’s “assertions” are “unhelpful”, Hito Steyerl’s writing is “brilliant”), reducing the paradigm of research to a matter of personal preference (Byrt, is after all, essentially a journalist and not an academic).[18]While Denny’s position may be difficult to ascertain, in the aforementioned aside, Byrt expressly endorses art theorist Mackenzie Wark’s (to put it blithely)meaningless notion of “vectoral capitalism”, and Harris’ work concluding that: “we actually have abundant resources available to counter an economic structure that determines value through scarcity. For Wark it is data which has the potential to be used by hackers against the “vectoral” class. For Harris, it is what we might call “moral” resources – specifically love and empathy.”[19] Byrt writes that it is rare for Denny to make a declarative judgement regarding the material that he presents, explaining that his position is “honest” in “(highlighting) the status of the artist in late capitalist culture: the contradictory desire to be a freelancer and entrepreneur on the one hand and a voice for resistance and progressive change on the other.”[20]Denny, for his part, identifies as a sculptor,[21]marking these works out as something static, the archive and game design evoked for neither’s informational properties but as aesthetic… even the art critic/academic as aesthetic: meaning as sculpture.

Évariste Vital Luminais, “The Sons of Clovis II”, 1880. Oil on canvas. 190.7 x 275.8 cm. Art Gallery of New South Wales.

THE MEROVINGIANS II (The French are not Franks):

Luminais was referred to variously as the painter of the Franks and the Gauls; in “The Sons of Clovis II” and its sister-work “Les Enerves Jumieges” (the two of which were the most successful and celebrated of Luminais’ works apparently for being so arrestingly macabre), the Frankish Merovingian dynasty is depicted to impress a sense of the particular brutality of that lineage. This subject was popular in 19th century France (after the initial Revolution and in the following period of instability) for its perceived justification of the “Reign of Terror”, as it was widely held that the Gauls had simply been restored to their rightful position as rulers of France, after centuries of Frankish rule (the Franks were of Germanic origin unlike the Gauls whom the French public widely identified as the descendants of).[22]In an article entitled “The Merovingians from the French Revolution to the Third Republic” historian Edward James writes of the extent of the efforts to characterise the former ruling dynasty as somehow ethnically violent. He explains that much to the annoyance of many of his contemporaries, François Guizot, “the leading figure among the liberal historians of the Restoration period,” introduced his own spelling of Frankish personal names, “The familiar ‘Clovis’, for instance, disappears in favour of Hlodewig. The purpose of this was clear: by going back to what he imagined the original Frankish form of the words was, he persuaded his readers to think of the Franks as foreign conquerors, rather than as comfortably assimilated Frenchmen.”[23] James also offers that the express purpose of teaching history at school, according to eighty percent of candidates for the baccalauréat moderne in 1897, was to instil a sense of patriotism.[24]Meanwhile, in the 19th century, “Gallic” France was nevertheless brutally suppressing colonised populations across the globe.

THE DREAD HISTORY PAINTING: [25]

“History Painting” existed long before the 19th Century but takes shape as a self-conscious form in that time as the invention of photography, combined with exposure to art from the rest of the world, seems to have caused some self-reflexivity regarding both the subjectivity and formal aspects of art within Europe.[26]Pre-19th century European art was, of course, dictated by financial and social limitations which meant that art centred around roughly the same themes of the prizes at AGNSW: representative images of the social elite; landscapes; or images of religious themes and/or European history from antiquity onwards. To have the history of European art laid bare so laconically, has long been an annoyance for Australian artists trying to function in a global continuum.[27]

There is perhaps something lost in the slippage between intent and actualisation that may be what makes the work of both eras of “Academic Art” so widely disliked.[28]The technical prowess of history painters such as Luminais never made up for how bland and somehow bad the paintings are, just as the (usually computer-generated) technical proficiency and sound logic of Post-Internet Art does not always quite add-up to satisfying work. I would refer to two articles published by Melbourne-based art publication MeMO about very different exhibitions. Lecturer in art history and theory at Monash University, Luke Smythe writes admiringly about John Martin’s (History Painting) “The Destruction of Pompei and Herculaneum,” 1822,[29]which was a work that people once paid a fee to see and experience (a kind of 19th century equivalent of watching the apocalyptic Netflix series “Stranger Things”)[30]. Of course, Martin was both exceptionally popular and very widely derided in his own time (William Makepeace Thackeray called his work: "huge, queer and tawdry").[31] A Martin retrospective in Newcastle (in the United Kingdom) caused these historical debates to be raised anew, but it would seem that in Melbourne, Smythe was simply taken with the grandeur and spectacle (not that there is anything wrong with that). It is the changing expectations for painting that are interesting here, and perhaps the fashion of the moment is such that many of these 19th century works will be assessed anew. In another review for MeMO, Gemma Topliss writes about Petra Cortright’s recent Post-Internet Art exhibition, describing it as belonging to the nostalgia for such things as “American Apparel tennis skirts, Lana Del Rey, washed-out digital images à la Terry Richardson, and blogging”[32], as though it goes without saying that art is necessarily subject to the whims of fashion. Cortright’s “paintings” made in Photoshop and printed on aluminium embrace newness and technology above all else, reducing the long painting tradition of contextualising one’s practice within the continuum, to absurdity. Topliss states that: “The aluminium is reflective and the paintings glow like dull screens, catching the light at certain angles to produce a luminous flash. They float, impossibly thin, like mounted flat-screen TVs.”[33] Much of the article refers to the artist’s desire to represent “beauty” in such a way as would be perfectly in keeping with the motivations of the most apparently backwards of painters/critics (of the kind that would take such prizes as the Archibald with the utmost seriousness). (Writing to a friend about the article on the Cortright exhibition I finally articulated my general feelings on the associated movement: “like most post-internet art, it seems interesting and possibly terrible”.) There are, however, outliers in any movement and History Painting has been alternatively used to call history into question (for purposes other than to rally Patriotism), Théodore Géricault’s critique of ultra-royalism, “The Raft of the Medusa” (also containing themes of abolitionism) comes to mind.[34]Post-Internet Art also transcends its modishness when it actually interrogatesthe present. Certainly, there is merit to works that allow for investment in research. There is, however, something missing when a work of art is only an argument. In the absence of a nuanced approach, we return to these problems: art as didactic panel, again without vestige of what originally animated a thing as art: that point at which human understanding fails.

WORKING CONDITIONS/ACADEMIC ART:

The work of Academic artists diverges from traditional academia due to the allegedly “subjective” nature of their/our work, meaning they/we are able to speak to more broad political issues. Best practice within academia is after all offering the complexities of a specific subject, even becoming expert by narrowing the field,[35]whereas artists will behave like bowerbirds taking ideas from everywhere and repurposing them. But in practice artists, too, tend to focus on very narrow fields as a means of self-marketing. Artist/Academics are bound by performance indicators and must seek public engagement as any academic, though with the added constraints of the art market, which would (famously) call for artists to simply reproduce the same works for sale. At the same time, there is a financial and social inevitability to the prevalence of “Academic Art” with so many artists becoming academics out of necessity, as less specialised work can no longer guarantee an income enough to keep up with the rapidly increasing cost of living.[36]Within the university, the increasing qualification requires PhDs of lecturers demanding a particular form of work and engagement, justifying itself through “research” paradigms originally designed for the sciences. Highly casualised and ultimately poorly compensated academic work is nevertheless highly sought after.

In a strange “debate” between anarchist anthropologist David Graeber and Peter Thiel, the two, though diametrically politically opposed, generally agree on a there being a cultural and scientific stagnation definitive of the present. Graeber, speaking to his experience in Anthropology departments in the U.S.A. and London gives a breakdown (mostly) endorsed by Thiel, which could equally describe the working conditions of artists/curators within Contemporary Art Institutions: “…in social theory, basically what we’re doing is writing these endless annotations on French theory of the 1970s, sometimes the 1960s or ‘80s. I call it the “Classic Rock Phenomenon” (…) if you want to have maximized possibility of unexpected breakthroughs it’s pretty obvious what the best policy is, get a bunch of creative people, give them the resources they need for a certain amount of time (…) basically you leave them alone. Most of them will probably not come up with anything but a few of them will come up with something that will even surprise themselves. If you want to minimize the possibility of unexpected breakthroughs take those same people and then tell them they’re not going to get any resources at all unless they spend the majority of their time competing with one another to prove to you they already know what they’re going to create...”[37] Art schools similarly function in the continuum of (predominately) French theory from around the 1970s, as well as referring almost exclusively to artworks from the same period. At Sydney College of the Arts, for example, there is a Second-Year assignment called “Art In The Expanded Field”, after the Roslind Krauss essay, “Sculpture in the Expanded Field” (published in October Magazine in 1979).[38]The essay refers to “Land Art”, much of which has been recently reassessed in terms of environmental impact, as well as the colonial aspect of reshaping the natural world (especially in unceded territory such as North America). Recent articles on Michael Heizer’s monumental structure “City”, for example, in (left political magazine) Counterpunch[39]and (online art publication) Hyperallergic[40]thereafter, question the merit of building an empty monolith in proximity to a site of significance for Native Americans. The original article seems dated and somewhat wrongheaded in arguing for this “new” art that Krauss expressly places above the proposed utility of spiritual sites such as Machu Picchu, in arguing for this art pour l’art… (or art for rich, white men with tractors).[41] Of course, all Land Art is not equal (Agnes Denes’ “Wheatfield”, 1982, has aged very well, in evoking food scarcity, for example). Within the framework of the university-based art school, it is not the merit (or lack) of the Land Art movement that is important so much as the oddly stagnant cultural assumptions, still perceiving the work of the 1970s as the work that is current, where art must be a grand gesture of contemporaneity in line with the production of spectacle. “Sculpture in the Expanded Field” had a significant impact on the way that we understand art, and yet perhaps what is perhaps a more interesting question, some 40 years later, is what art is not in ‘the expanded field’? In a sense the purported newness of this method of working serves to undermine art historical works, continuing the strange antagonism between “Painting” and “Contemporary Art”, as though painting never exists/ed in the world. The fetishism that is encouraged in schools of painting (the glorification of oil paint and stretched canvas as though one could not possibly make anything of value with the wrong pigment) undermines the art historical works it simultaneously glorifies, for, what work of “the canon” is canonised for being simply well-executed? Many paintings that remain admired from the Renaissance are still relevant for having worked within the narrow confines of Christian art to produce something outside it, in ways that were often subversive. Titian’s “The Tribute Money” (around 1516), is an interesting example, painted for the door of the Duke of Ferrara’s famous coin collection. As explained in the didactic panel at The Old Masters Gallery in Dresden: “The subject here is the provocative question posed by the Pharisees as to whether it is right to pay taxes to the Emperor in Rome. Christ cleverly avoided the trap by asking for a coin bearing the head of Emperor and saying “Render to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s and to God the things that are God’s…”” While the theme is certainly suitable for its destination, there is also something fundamentally subversive about rendering a coin collection, a display of wealth, with the image of Jesus in the act of demonstrating the ungodliness of money.[42]

THE “NEW” ACADEMY:

In the 19th century, History Painting/Academic Art functioned as Academic/Post-Internet Art does today in prosaically and proficiently illustrating its didactic ends, though it could be conceded that the patriotism of the original movement is in diametric opposition to motives of contemporary academia with its (at least generally stated) anti-imperial and postcolonial ideals.[43]Denny’s ambivalent position, even lack of a (at least visible) position enables him to work within the Contemporary art market and broader neoliberal framework in a way that has demonstratively been revoked from increasingly-threatened disciplines within the Humanities, whose overtly antagonistic positions have regularly been cited by (at least) the Australian Liberal Party as a threat in (the rather more banalised Australian version of) “the culture wars”.[44]Of course, extremes of anti-imperial discourse have been repeatedly instrumentalised in justifying university cuts everywhere (that belong to a greater trend towards austerity). In her 2021 polemic “Virtue Hoarders: The Rise of the Professional Managerial Class”, academic Catherine Liu writes of a well-funded conspiracy within North American universities to create an ahistorical counternarrative so extremely (and alienatingly) to ‘the Left’ as to promote individualism and relativism over working-class consensus, concluding that: “Liberals have abandoned history, because they have to believe they are superior to elites of the past and the contemporary working class at the same time. Members of the PMC (Professional Managerial Class) believe themselves to be virtuous vanguardists, floating above historical forms and conditions, transgressing boundaries and inventing new ways of being and seeing.”[45] It is possibly the idea of “the new” that is ultimately so troubling. It is difficult to overlook that Denny’s research comfortably fits within the ideology that it ultimately promotes understanding of, whether or not the conclusions are flattering.[46] The result is a kind of Warhol-esque flatness. It represents and engenders contemporary ambivalence. (I can never figure out if I love it or hate it, but, ironically, it does make me feel something.)

HAND-DRAWN CONCLUSIONS/HISTORY IS WRITTEN BY THE VECTOR:

Strangely, it is the dearth of education in art history that leads to these ghosts of historic forms, this ‘universal’ European continuum. The failure to learn to appreciate the trajectory of Western art history (and the history of Western thought in general) has led to a stagnation in mainstream Western culture further exasperated by income inequality and the corporatisation of universities (both public and private). Art schools may have been among the first in the university to jettison tradition for the sake of “relevance”, to where the focus has become near chronophobic, perpetuating only iconoclastic works of the 20th century that purport to exist outside of the economic system, outside of national boundaries. In Western cosmology, the obsession with the “new” serves to impress the idea that the human can be perfected alongside technology. Though artists such as Denny are very informed regarding art history, Post-Internet Art is institutionalised (by Museums and Academia, though mostly the market) to sometimes critically observe the effects of Technocracy on society and sometimes embrace this new era, but always to privilege technology in line with the ideals of the Technocracy. This kind of art now commands immense profit in corrupt markets that encourage insider-trading, further exasperating the unequal distribution of wealth. Now every university department must demonstrate that it can be similarly instrumentalised or face inevitable decline (in a strange turnaround, Sydney College of the Arts is doing very well economically). Academic Art may demonstrate some value in encouraging and visualising forms of closer reading that are now considered an indulgence, but in this “information age” more knowledge is being lost by economic conditions than can ever be replaced. It is in this historical myopia that we may discover why the present seems so insurmountable.

This Ekphrasis//Ekphrasis Project will continue via Substack: @zoemarnirobertson

Zoë Marni Robertson is an artist, writer and Sessional Academic/PhD candidate at The University of Sydney (SCA). Zoë's research-based work encompasses video, painting, prose, poetry and performance, often using found materials. She has exhibited across a wide network of Artist-Run-Initiatives as well as various Institutions such as The Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney (MCA) and The Murray Art Museum, Albury (MAMA).

Instagram: @zoemarnirobertson

[1]David Brooks, The Sons of Clovis: Ern Malley, Adoré Floupette and a Secret History of Australian Poetry, St Lucia, Qld: University of Queensland Press, 2011.

[2] Ian Milliss’ Facebook

[3] It sometimes feels as though half my generation of Antipodean artists left for the greener pastures of Europe, accepting the notion that we are at the edge of the earth, that Europe and North America (or Berlin and New York) are at the centre of art.

[4] Actual exhibition texts written by Anthony Byrt are hard to come by outside the “Founders Paradox Compendium” sold by Denny’s Auckland-based gallery, Michael Lett, so the story, and subsequent appearances by antagonist Peter Thiel would seem to now be archived solely in this “long read” by Mark O’Connell, “Why Silicon Valley billionaires are prepping for the apocalypse in New Zealand”, The Guardian, 15 February 201, https://www.theguardian.com/news/2018/feb/15/why-silicon-valley-billionaires-are-prepping-for-the-apocalypse-in-new-zealand

[5] James Duesterberg, “Among the Reality Entrepreneurs: Urbit goes downtown”, The Point Magazine, September 9, 2022, https://thepointmag.com/examined-life/among-the-reality-entrepreneurs/

[6] O’Connell ibid.

[7] Duesterberg ibid.

[8]Thomas Coughlan, “Thomas Coughlan: The brilliance of The NZ Project,” Newsroom, April 26th 2017, https://www.newsroom.co.nz/2017/04/25/20680/thomas-coughlan-the-brilliance-of-the-nz-project last accessed: 17/08/2023

[9] O’Connell, Ibid.

[10] O’Connell ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] This is (likely intentionally) reminiscent of the popularity of the game “Monopoly” which was, of course, designed as a tool for demonstrating inherent ills of capitalism only to become uncritically accepted as a fun pastime.

[13]Brue Bartlett, “Keynes Was Really A Conservative”, in Forbes Magazine,August 14 2009, https://www.forbes.com/2009/08/13/john-maynard-keynes-conservative-opinions-columnists-bruce-bartlett.html?sh=60148e837605

[14] I have not yet read it, and I am a big fan of The Welfare State.

[15] O’Connell ibid.

[16] Danyl Mclauchlan, “The New Zealand Project offers a bold, urgent, idealistic vision. I found it deeply depressing”, in The Spinoff, April 22, 2017, https://thespinoff.co.nz/politics/22-04-2017/the-nz-project-offers-a-bold-urgent-idealistic-vision-i-found-it-deeply-depressing#.WPp69pyGTEg.twitter

[17] Anthony Byrt and Simon Denny, “The Founder's Paradox: A Compendium”, Michael Lett Gallery Publications, 2017. P. 9 Quote in: Byrt, Anthony. This Model World : Travels to the Edge of Contemporary Art, Auckland University Press, 2016. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/usyd/detail.action?docID=4689774.

Created from usyd on 2023-08-27 01:32:40. P.195

[18] Byrt and Denny Ibid, p.40.

[19] Ibid.

[20]Byrt, Denny Ibid. p.10

[21] Ibid.

[22] Citizen Ducall asked for the abandonment of the word ‘French’ – ‘we are pure blood Gauls’ – while Anacharsis Cloots wrote in 1793 that ‘The French have emigrated or been guillotined. The Gauls have become men by crushing their conquerors under the ruins of the Bastille.’ James, Edward. “The Merovingians from the French Revolution to the Third Republic.” Early Medieval Europe 20, no. 4 (2012): 450–71. https://doi.org/10.1111/emed.12004.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Ibid.

[25] On general disdain for Academic Art/History Painting, take for example, an article on the legacy of Gustave Moreau: “Dictionaries, encyclopedias, and histories of art associate Gustave Moreau with fin de siecle Symbolism or Decadence. While this categorization has undoubtedly helped to save Moreau's oeuvre from the oblivion in which despised nineteenth century "academic" art lay for so long, it has also distorted our understanding of his achievement. Art historians are now beginning to recognize an essential fact that was self-evident to Moreau himself, as well as to his contemporaries: the author of Oedipus and the Sphinx and Salome was, above all, a history painter.1 Indeed, not only did Moreau proudly describe himself as "peintre d'histoire" on his visiting cards but also, to the end of his life, both as a practitioner and as a teacher, he maintained an unshakable loyalty to the ideals traditionally associated with the genre that he preferred to call "le grand art."” Cooke, Peter. “Gustave Moreau and the Reinvention of History Painting.” The Art Bulletin 90, no. 3 (2008): 394–416. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20619619.

[26] As the 20th century would see Western artists diverge from tradition by appropriating themes from “other” cultures, particularly from African art and Eastern Philosophy.

[27] It is slightly mortifying… and yet also very funny when one considers how much North American and European Art of the 20th century aimed to present itself as universal and “new” while stemming from exactly this narrow European tradition. If this is quite a nihilistic perspective it is perhaps fitting in the context of the feeling of cultural stagnation, which I believe to stem from material shortcomings, i.e., the unequal distribution of wealth, rather than any inherent lack on the part of artists of the present.

[28]In a podcast hosted by Joshua Citarella, curator of KW Institut in Berlin, Nadim Samman discusses his new book on Post-Internet Art making reference to a time “Before Post-Internet Art was a dirty word.” Joshua Citarella with guest Nadim Samman on Substack “Cryptids and Conspiracy in the Technocene w/ Nadim Samman”

[29] Luke Smythe, “Light: Works from Tate's Collection” MeMO Review, 6th August 2022. https://memoreview.net/reviews/light-works-from-tate-s-collection-at-australian-centre-for-the-moving-image-acmi-by-luke-smythe

[30]John Gayford, “John Martin: the Laing Gallery, Newcastle” March 15, 2011. The tagline for the article is: “John Martin, the subject of a new exhibition, was a painter whose apocalyptic visions prefigured Hollywood.”

[31]Mark Brown “Derided painter John Martin makes a dramatic comeback” in The Guardian, March 4, 2011

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2011/mar/04/artist-john-martin-comeback

[32]Gemma Topliss, “Petra Cortright, haunted lemon hunted spirit” MeMO Review

[33]Ibid.

[34] I am indebted to Alex Gawronski for the suggestion.

[35]As pointed out by Umberto Eco: “Finally, remember this fundamental principle: the more you narrow the field, the better and more safely you will work. Always prefer a monograph to a survey. It is better for your thesis to resemble an essay than a complete history or an encyclopedia.” Umberto Eco, How to Write a Thesis, MIT Press, 2015. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/usyd/detail.action?docID=3339948. Created from usyd on 2022-05-18 01:59:57 P.13

[36] See Liu Ibid.

[37] “David Graeber vs Peter Thiel: Where Did the Future Go" David Graeber vs Peter Thiel: Where Did the Future Go - YouTube

[38] Krauss, Rosalind. Sculpture in the Expanded Field. October. Vol. 8. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 1979.

[39] Char Miller, “Monstrosity in the Nevada Desert: Michael Heizer’s “City””, in Counterpunch, August 26, 2022. https://www.counterpunch.org/2022/08/26/monstrosity-in-the-nevada-desert-michael-heizers-city/

[40] Chris Fernald, “Michael Heizer’s Empty Empire,” Hyperallergic, September 26, 2022.

[41] The Krauss essay itself is (somewhat more sensitively) critiqued by Jan Verwoert and Hugh Rorrison in the article: “Why Are Conceptual Artists Painting Again? Because They Think It’s a Good Idea.” Afterall 12, no. 12 (2005): 7–16. https://doi.org/10.1086/aft.12.20711583.

[42] At the National Gallery in London, beside a later version of the painting, the didactic panel reads “Asked about paying taxes, Christ identifies Caesar’s name on a coin, noting that it belongs to his government, thereby emphasising that taxes are not in conflict with his teachings…” which seemed quite a funny way of neutralising the work, though I am no theologian.

[43] History Painting of the same kind practised in the 19th century, of course, still exists, its trajectory from Ancient Greece to Modern Europe and North America make it the kind of art favoured by American Conservative to this day. It is also the major theme of Australian art prizes; aside from the Archibald there is the Portia Geech, The Dobell, etc. There will always be people working within outmoded continuums, but these are not of interest to us here.

[44]See, for example, discussions between former Prime Minister Tony Abbott and late businessman Paul Ramsey which resulted in the founding of “The Ramsey Centre for Western Civilisation”, which was supposed to infiltrate the Australian National University, but has ended up at the University of Wollongong. As claimed by Abbott: “every element of the curriculum was supposed to be pervaded by Asian, indigenous and sustainability perspectives. Almost entirely absent from the contemporary educational mindset was any sense that cultures might not all be equal and that truth might not be entirely relative.” As quoted by Mike Seccombe, in “Howard, Abbott and the Ramsay Centre” in The Saturday Paper, June 16-22 2018, https://www.thesaturdaypaper.com.au/news/politics/2018/06/16/howard-abbott-and-the-ramsay-centre/15290712006378

[45] Catherine Liu, ““Transgressing” the Boundaries of Professionalism” in Virtue Hoarders: The Case against the Professional Managerial Class. University of Minnesota Press. 2021 https://doi.org/10.5749/j.ctv1fkgbjxp.34.

[46] As written by (former academic) philosopher, literary theorist, and political theorist, Armen Avanessian: “(Criticality) criticises within the system, but it does so without assenting to the system as such, aware that an absolute position outside the system is impossible, and that even the most radical criticism has a legitimate legitimising affect. The “smuggling” of embedded criticism thus names the strategy of sidestepping or going behind an order and of hollowing out legitimacy from the inside. Imminent criticality takes pleasure in the self-reflexive paradox of holding on to a subversive behaviour it knows to be unsustainable.” Armen Avanessian, Overwrite: Ethics of Knowledge—Poetics of Existence, London: Sternberg Press, 2017. P.38.

“Subject” at The University of Sydney (Gallery in the Sky Bridge)

“Representation of Dead White Men”, MMXXII. Acrylic (house paint mis-tints) on (discarded) canvas (banner). Approx. 5000 x 2000 mm.

“Atropos, The Countess of Lopfen”, MMXXII. Acrylic (house paint mis-tints) on (discarded) canvas (banner). Approx. 5000 x 2000 mm.

(Goya’s “Atropos, the Fates” conflated with a probably apocryphal story from the German peasant war of 1525, in which the Countess of Lopfen demanded that 1200 of her serfs find her snail shells to use as spools for her thread... the fates, of course, would spin the thread of a man’s life and Atropos would cut it at its end.)

“Technofeudalism II: Great Replacement”, MMXXII. Lime wash on (discarded) poly/cotton (bedsheet). Approx. 2100 x2100 mm.

(Elon Musk and his many children... he keeps talking about population collapse but any demographer will tell you that it’s not a thing... exept in the European population... gross.)

“Cephalophore, Cure for M.E. (Myalgic Encephalomyelitis)”, MMXXII. Oil on canvas. 1016 x1016 mm.

“Paleo Monolith on Neolith”, MMXXII. Oil on canvas. 1016 x1016 mm.

(Neolith is a kind of “engineered stone, of the kind that keeps giving stonemasons silicosis. The meat is a painting of Paul Thek’s “Meat Piece with Warhol Brillo Box”.)

“Eddy” and “Gelato Cafe” with Minerva Gallery

Group exhibitions in pop-up galleries “Eddy” and “Gelato Cafe” with Minerva Gallery, November/December MMXXII

Eddy:

“ Design Classic: Control (Nostalgia for a Future)”, MMXXII. Acrylic on (found) masonite. Approx. 1210 x 1210mm.(3 figures)

“ Design Classic: Control (Mutually Assured Destruction)”, MMXXII. Acrylic on (found) masonite. Approx. 1210 x 1210mm. (Singular figure).

“Technofeudalism II: Great Replacement”, MMXXII. Lime wash on (discarded) poly/cotton (bedsheet). Approx. 2100 x2100 mm.

(Elon Musk and his many children... he keeps talking about population collapse but any demographer will tell you that it’s not a thing... exept in the European population... gross.)

“Technofeudalism I: Meta Cephalophore”, MMXXII. Lime wash on (soiled)(discarded) cotton (bedsheet). Approx. 2100 x 2100. (Work in foreground by Phillipa Hagon).

Gelato Cafe:

“ Habeas Corpus (You Should Have the Body) ”, MMXV.Discarded lime wash and enamel on discarded canvas. (Work in foreground by Phillipa Hagon).